Introduction

So that young generations can learn to solve challenges related to the complex and ever-changing world of the 21st century, we need to prioritise education that focuses on active learning and problem-solving skills (Rubini et al., 2020). One option for developing such skills is an approach called problem-based learning, which is the main premise of this article.

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a method based on students’ active role in learning. This employs student-centred learning where students are presented with a real-life problem that they work on resolving together in small groups, using their shared, preexisting knowledge and experience to identify facts and knowledge gaps, and acquiring new knowledge to further understand the topic and eventually propose a solution (Ghani et al., 2021). Since its initial application in the 1960s in the field of medicine (Hmelo-Silver, 2004), PBL has been implemented in a variety of educational sectors. The most recognised benefits of the method include a plethora of student-developed competencies: collaboration and teamwork skills, problem-solving and analytical thinking, communication, flexible and interdisciplinary knowledge, independent learning, and a more positive attitude towards learning, which in turn affects the students’ motivation (Lee & Jo, 2023). On the other hand, there are also several widely-recognised disadvantages and challenges to PBL. For example, PBL is often time-consuming and resource intensive, as it requires supervision by trained staff. Another recognised issue is that knowledge acquisition might not be the same for all students under PBL. This is because some people are highly individual while others are strongly opinionated, which can result in unequal participation and inconsistent learning (Abdelkarim et al., 2018). It is also important to understand that in this approach the teacher’s role is transformed into one of a tutor, or a mentor, who facilitates the learning process by guiding the students and offering advice (Ghani et al., 2021).

The aim of this article is to examine the students’ perspective of the PBL process that was applied during the student challenge Developing a Sustainable Tissue Culture Banana Value Chain, which was organised by the AgriSCALE project. The study in this article is based on analysing the positive and negative feedback from the students participating in the challenge, as well as their improvement suggestions, which will all together provide important insight into organising any similar challenges in the future. A student challenge such as this includes students and tutors from partner universities who are selected to work together. These learning opportunities use the PBL approach on a problem proposed by a real-life client, for instance, a company or an organisation, with the aim of improving the students’ employability as well as strengthening the connection between university education and the industry (Määttänen et al., 2022). The student challenge in question, Developing a Sustainable Tissue Culture Banana Value Chain, was focused on the entire value chain – including production, marketing and farmers – of tissue culture bananas, that is, banana plantlets propagated asexually from different parts of the plant, resulting in a high number of plantlets that are free from diseases and pathogens (Sivaji et al., 2020). The student participants interviewed representatives from the value chain, with the goal of improving the working methods used in the value chain and thus increasing the popularity of tissue culture bananas in the central region of Kenya.

Methods

The student challenge, which took place at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT) in Nairobi, Kenya, in October 2023, was attended by 27 students and 9 tutors from 5 universities: Häme University of Applied Sciences in Finland (HAMK), Egerton University (EGU) in Kenya, Bishop Stuart University (BSU) and Gulu University (GU) in Uganda, and the organising university itself. The author of this article was one of the mentors.

All of the 27 students taking the challenge were invited to participate in this study. A voluntary response sample of 13 chose to participate, representing 48% of the entire student group.

The study was conducted in the form of an anonymous, semi-structured online questionnaire that consisted of 11 questions. The questionnaire was constructed in Microsoft Forms prior to the beginning of the challenge, and it was distributed to the participants on the 27th of October 2023, approximately one week after the end of the challenge, via a student WhatsApp group. All the students attending the challenge were members of this chat group, so they were free to choose whether to answer or not. Responses were accepted for a period of one week, until the 3rd of November 2023. The questionnaire description also included a link to a privacy notice, which detailed the handling of the collected data.

When the data collection was finished, the data was downloaded from Microsoft Forms into Microsoft Excel, where all the answers were reviewed and analysed. One respondent was removed from the sample of responses due to being a duplicate.

The data analysis, conducted in Microsoft Excel, began with a descriptive analysis of the demographic data and continued with a thematic content analysis of the open-ended questions. During the content analysis, all of the answers were first read to get a general idea of the answers, after which common themes were identified and assigned to each response. The first part of the questionnaire, where students responded to Likert-scale questions on statements about the relevance of the learning opportunity (for details on the questions, see figure 3), was analysed using a deductive approach. After this, the second part with open-ended questions included answers to about likes, dislikes and suggestions. These were analysed using inductive qualitative coding, a systematic approach where specific objectives guide the summary of raw and extensive text with labels (Thomas, 2003). This was performed on paper and transcribed into a new Microsoft Excel sheet. Subsequently, quantitative content analysis was performed to provide understanding of the students’ experience. The results of the data analysis were tabulated and graphed, and the following section reports on these results.

Results

At the beginning of the questionnaire, 85% (11) of the participants agreed that they considered a PBL student challenge different from their previous learning experiences. In terms of demographic information, the age of the participants ranged from 20 to 35, with the average age being 26, and 38% (5) of the respondents were male and 62% (8) were female. When it comes to university representation, the respondents consisted of 3 students from JKUAT, GU and EGU each, and of 2 students who responded for both HAMK and BSU, leading to a relatively equal representation of all the attending partner universities. In terms of student motivation for completing the questionnaire, it is important to note that the participants were not offered any compensation for responding.

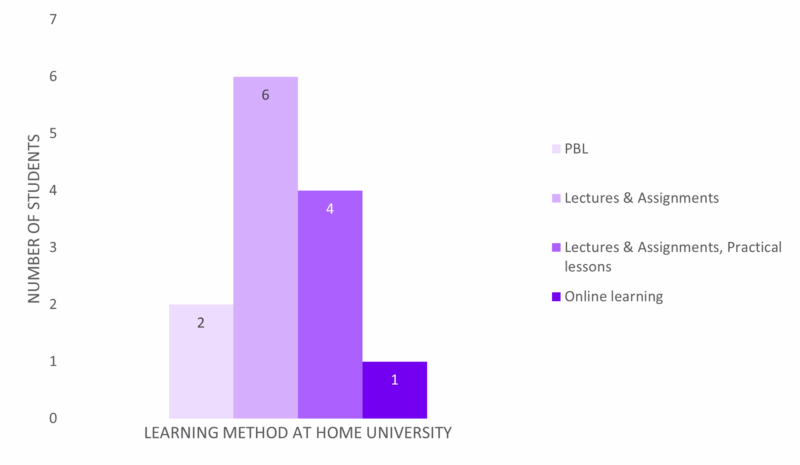

When asked how learning was usually conducted at their home institution, 46% (6) of the students listed lectures and assignments in their answers, with 31% (4) specifying that these approaches to learning were also supplemented by practical lessons, as shown in Figure 1.

The nature of lessons was described as “typically delivered to large groups of students” or “very informative but also quite passive.” Only 8% (1) included online learning in their response, and PBL was mentioned only by 15% (2) of students. In addition to this, one respondent mentioned that their home university was “trying to promote PBL,” although they did not consider this as the usual method of delivery during lessons.

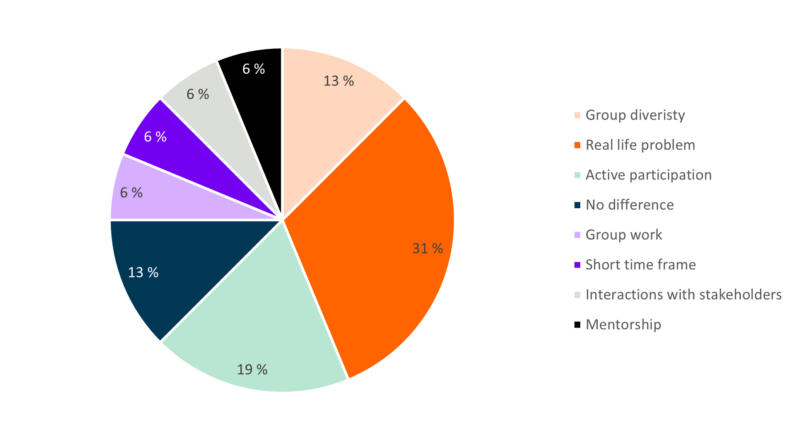

Furthermore, the participants were asked to specify what the difference was, if any, between PBL and their previous learning experiences (Figure 2). The answers varied greatly, as some students mentioned more than one difference. However, the most common differences that they noticed were working on a real-life problem (38%, 5 students), the opportunity to actively participate in the learning process (23% – 3 students), group diversity both culturally and academically (15%, 2 students), and only 15% (2 students) replied that there was no difference to their previous learning experiences. In this part, the differences to previous experiences that were mentioned only once included group work rather than individual work, direct interaction with stakeholders, the presence of mentors, and an opportunity to try working in a limited time frame. While some answers were very general, a few respondents elaborated on the differences in more detail. For example, one student reasoned that “you get to solve a problem in the value chain by actively participating [rather] than just by listening to it and getting to write what other people have worked on” and that “each student had different skills which was crucial.”

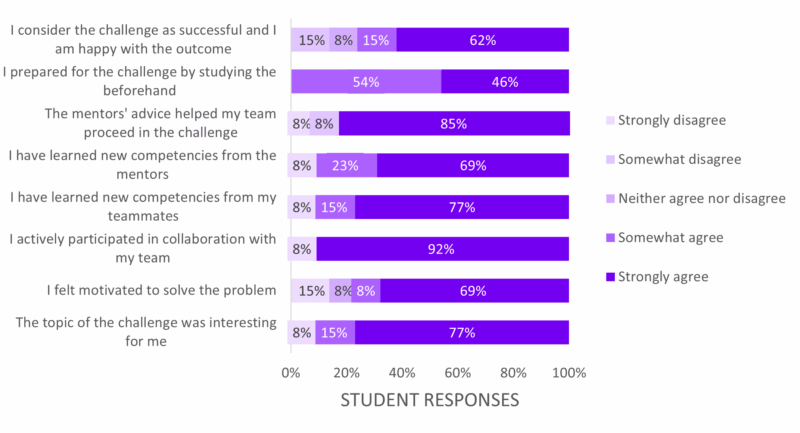

In general, the students had a positive perception of, and attitude towards, PBL in the context of the student challenge. This is apparent from the students’ responses to the Likert-scale questions where most indicated that they agreed either “strongly” or “somewhat” with the positive statements. Further details on this can be seen in Figure 3 below:

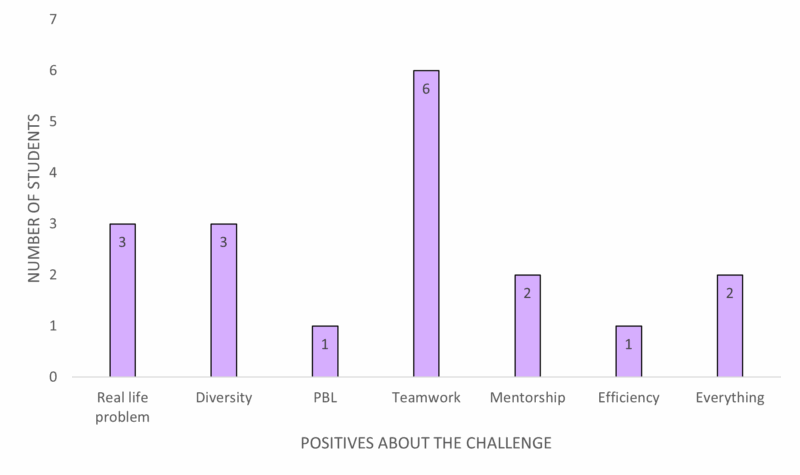

In the case of the second part of the questionnaire, which contained three open-ended questions, many students mentioned more than one thing, and the feedback was varied when they were asked what they liked about the challenge (Figure 4). Teamwork was most often mentioned as a positive aspect of the PBL approach, altogether by 46% (6) of respondents. At this question, the students expressed their appreciation of “working as a team regardless of our backgrounds” and “great teamwork and great collaboration.” Working on a real-life problem and the diversity of the groups were both mentioned by 23% (3) of the students, for instance, appreciating “the fact that one could interact with students and mentors from other disciplines and appreciate different ways of viewing matters.” Mentorship and “everything” was stated as a positive by 15% (2) of the students. Lastly, PBL methods and the efficiency, or the short duration period of the learning opportunity, were each liked by 8% (1).

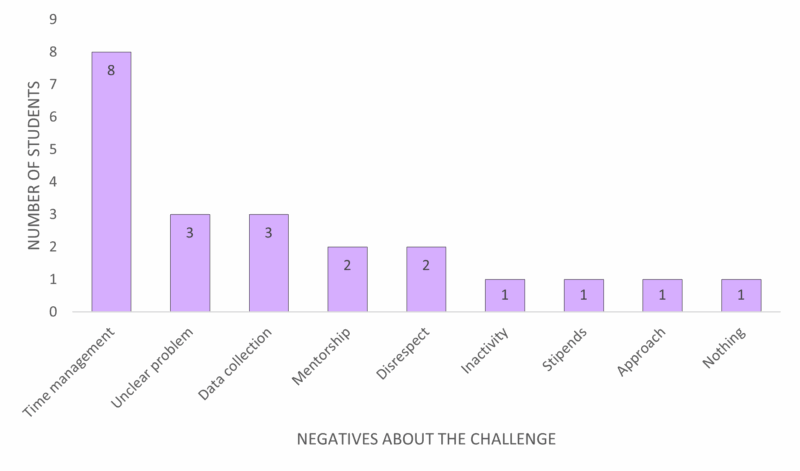

Answers to the questions about dislikes were much more diverse (Figure 5). 62% (8) of respondents mentioned time management as a negative, reporting that “there was a lot of waiting with unclarity of what we waited [for]” and pointing out that the way how time is used should be planned further so that “at least the online platform should be utilized more.” The data collection and the insufficient clarity of the problem were each disliked by 23% (3) respondents, saying that “meeting farmers once and as a group” was not ideal, and that “we should visit more challenge owners i.e. marketers for better results.” Some respondents also noted a “lack of sync between what cooperative and farmers expected and what we conducted” and that “the challenge was obscurely described by the challenge owners.” Also, mentorship and disrespect were both mentioned by 15% (2) of respondents, stating that “the mentors were not aligned between themselves” and that also the participants should show more respect among themselves. Lastly, the following categories were mentioned as negative things by only 8% (1) each: inactivity (where “[s]ome students did not participate [in] teamwork, but this was not addressed by mentors”), stipends, and approach. In this category, one respondent also left this reply empty, suggesting there were no dislikes.

In the last question, the students were asked to give suggestions or report anything else that they wanted to share. These responses included a variety of categories, as some chose to express additional positive/negative feedback, some provided suggestions and new ideas, and others chose not to suggest anything. As for recurring themes in the responses to this question, 23% (3) students mentioned their appreciation for the multicultural working environment, 15% (2) praised the team setting, and 15% (2) were happy about the academic freedom they experienced and the fact that they could use their own reasoning, saying that “the challenge helped students be more creative and reason deeply.” In addition to this, 15% (2) students suggested that each team should have been allocated one mentor for the entire duration of the challenge. Further suggestions included allocating more time for the challenge, improving the utilisation of online work prior to the challenge, providing more information about the PBL method itself, creating better alignment in how the work will be conducted (e.g., clearly deciding if laptops should be used or not), and improving the mentor guidance.

Discussion

The pool of respondents well represents all of the students from different universities who participated in this specific student challenge. The results indicate that more than three-quarters of the respondents did not have any previous experience with the PBL method and that they were instead more accustomed to traditional learning methods, such as lectures, assignments and practice lessons. Despite their lack of previous experience, the students expressed many positives when asked how they saw the PBL method as different from what they had experienced until then. All in all, their responses showed appreciation for the group diversity, both in terms of culture and study field, and they liked the opportunity to actively participate in the learning process and the chance to work on a real-life problem originating from the surrounding society. This analysis of the what the students like and dislike illustrates that they are particularly keen on teamwork, diversity, and solving real-life problems. On the other hand, more than half of them expressed dissatisfaction with time management during the learning opportunity, the used data collection method, and what they felt was an insufficient clarity of the problem. Still, the data collected from the Likert scale shows a positive trend as most students felt motivated and interested in the topic, and they agreed to the statement of having learned both from their teammates and the mentors. What is more, everyone stated that they prepared prior to the challenge and majority was happy with the results of the challenge. Overall, the data suggests that the students perceive the challenge in a positive light, while still being able to point out what could be improved for next time. It seems that the methods and the diverse team setting make the challenges particularly attractive and engaging, while a significant improvement in organisation is needed to make the experience even better. This is valuable insight that can be useful in conducting any similar future challenges.

The results are well in line with the findings of Määttänen et al. (2022) who conducted a similar questionnaire evaluating the students’ perspective after piloting these kinds of student challenges in 2021. Their respondents regarded the challenges in a positive manner, expressing their appreciation for teamwork and real-life connection, as well as their motivation to solve the challenge. In the case of this pilot by Määttänen et al., the students named inadequate individual preparation prior to the challenge and limitations of resources and time as the main obstacles to learning. Based on these results, the students’ awareness of the importance of individual preparation for the challenge has improved, while the same driving factors that make the experience worthwhile still exist. At the same time, resource and time management, especially when it comes to data collection, still seem to remain as hindering factors.

Based on the results of this case study, it can be recommended that PBL is implemented also for future groups of students who come from different cultural and educational backgrounds. In addition to teamwork as the most important factor of the PBL student challenge, the students were motivated to solve a real-life problem, meaning that also further challenges should be focused on problems that have a real impact on the local community. On the other hand, the scheduling and organisation of the challenges should be improved, as time management remains the most frequent complaint. The organisers should also define and prepare the challenge in more detail before it commences, to avoid unnecessary waiting which the students consider tiring and wasteful. In addition to this, lack of proper organisation in data collection, transportation, and the online part of the challenge contribute to poor time management and should be investigated. Additionally, information about the PBL methodology itself should be delivered to all student challenge participants at the beginning of the challenge. This could be done, for instance, online or at the very beginning of the in-person week, to make sure that everyone is familiar with the process and understands what is required of them.

It should be noted that the scope of this study is limited by the scale of the challenge itself, and that this study cannot be generalised to different projects due to its case specificity and small size of the response sample. Although the overall results seem positive, the data set is too small to provide any statistically significant results, other than a point of comparison to earlier reports about the same project concept. To overcome this limitation, a larger survey should be conducted in a way that includes the participants of all student challenges that HAMK has participated in since these types of projects were piloted in 2021. In this kind of a larger study, the potential number of respondents would be higher and thus sufficient to perform a statistically significant evaluation of the success of the challenges and the progress that has been made over time. This would also make it possible to design a longer, in-depth questionnaire to gain more detailed insights, which in turn would make the evaluation more comparable with other projects.

The reliability of the results in the present study may also be influenced by the participants’ understanding of the topics of each question on the questionnaire and by their subjective interpretation of these questions. For example, one respondent claimed the challenge was not different from their previous learning experiences while stating that learning at their home university is usually conducted through lectures, which implies either an insufficient understanding of the PBL methodology or an incorrectly worded series of questions. Furthermore, the strikingly positive results of the Likert-scale questions, and the fact that only positive things were mentioned when asked about the difference between PBL and pervious learning experiences, suggest a high likelihood of social desirability bias. That is, in this case the students’ tendency to provide answers that make them look good might have been influenced by the positive and direct framing of the Likert statements and the small-scale setting of the challenge itself.

Conclusion

Problem-based learning is a student-centred methodology that prioritises students’ active participation in their own learning experiences. This encourages the development of problem-solving skills, critical thinking, communication, teamwork and several other benefits that are essential in the 21st century.

The aim of this article was to analyse the perspective of students who engaged in problem-based learning through the student challenge Developing a Sustainable Tissue Culture Banana Value Chain, organised in Kenya in 2023 by the AgriSCALE project. This analysis was conducted with a view on better understanding the experiences and feedback on this specific learning opportunity, in order to improve the organisation of any future student challenges.

Based on the answers of the participants, it was clear that problem-based learning was not regularly practiced at their home institutions, as most students were used to lectures and assignments as the primary way of learning. In their responses on the main differences between their usual way of learning and the problem-based learning they experienced during this student challenge, the students listed active participation and teamwork, group diversity and working on a real-life problem as positive factors that they liked the most. The overall perception of the challenge and the learning methodology was also positive as the students reported feeling motivated and interested in the topic. On the other hand, the errors in time management, data collection and lack of clarity on the problem itself were viewed negatively – and as the biggest obstacles for learning. The insights into the students’ perspective on this learning experience, and the recommendations that can be given based on the results of this study, are essential for improving the quality of similar student challenges and projects.

References

- Abdelkarim, A., Schween, D., & Ford, T. (2018). Advantages and Disadvantages of Problem-Based Learning from the Professional Perspective of Medical and Dental Faculty. EC Dental Science, 17(7), 1073–1079. https://ecronicon.net/assets/ecde/pdf/ECDE-17-00707.pdf

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 235–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3

- Ghani, A. S. A., Rahim, A. F. A., Yusoff, M. S. B., & Hadie, S. N. H. (2021). Effective learning behavior in problem-based learning: A scoping review. Medical Science Educator, 31(3), 1199–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01292-0

- Thomas. D. R. (2003). A general inductive approach for qualitative data analysis.

- Lee, N., & Jo, M. (2023). Exploring problem-based learning curricula in the metaverse: The hospitality students’ perspective. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 32, 100427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2023.100427

- Määttänen, S., Knuutti, U.-M., & Laitinen, E. (2022, September 26). Piloting international student challenges: Results on students’ perspective. HAMK Unlimited Professional. https://unlimited.hamk.fi/ammatillinen-osaaminen-ja-opetus/piloting-international-student-challenges-results-on-students-perspective/

- Rubini, B., Juwita, L., & Aisyah, S. (2020). Problem-based learning on climate change theme: Concept mastery profile and problem solving skills of secondary students. 76–78. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200513.017

- Sivaji, M., Pandiyan , M., Yuvaraj, M., Thilagavathi, T., Sasmitha, R., & Suganyadevi, M. (2020). Micropropagation – Tissue Culture Banana. Vigyan Varta, 1(3), 28–32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361051601_Micropropagation_-Tissue_Culture_Banana

Authors

Lenka Siskova

HAMK graduate in Bachelor of Natural Resources; Climate Smart Agriculture programme. Participated as a student mentor in a project organized in Kenya.