ABSTRACT: Digital transformation initiatives in developing countries often overlook the linguistic realities of local populations. During XRTanzania project field research, as interviews were conducted with different ecosystem actors, a persistent language barrier emerged as a central but under-examined, factor shaping digital inclusion. Although Swahili (Kiswahili) is Tanzania’s national language and the primary language of instruction in public primary schools, many ICT learning materials, textbooks, and digital tools are available only in English despite efforts to use Swahili in teaching and learning in all subjects. There are also mixed-language ICT textbooks that use both Swahili and English. Furthermore, English-based keyboards and direct translations of English terminology create cognitive and practical obstacles for both teachers and learners. This study examines how these linguistic mismatches hinder the learning of pupils who are struggling with mastering English as their second language, resulting in a long and bumpy road from Swahili to screens. By analysing stakeholder insights and the structure of commonly used ICT resources, this study seeks to determine the extent to which language contributes to digital exclusion. The findings in this study highlight the need for more contextually relevant and linguistically accessible ICT materials, informing strategies for more inclusive digital transformation.

Introduction

In Tanzania, digital literacy is taught in primary education as part of Information Communication Technology (ICT). At this stage, emphasis is placed on the use of computers as the primary ICT device. The language of instruction in primary education is Kiswahili, and the English language is taught as a separate subject. While this creates the expectation that ICT should be taught in Kiswahili, in practice both English and Kiswahili are used. As ICT education becomes central to curricula (Hajati, 2022), the mismatch between the linguistic demands of ICT resources and the linguistic realities of teachers and students creates significant barriers to accessibility and effective classroom practice (Ntshauba, 2024). Learning relies on textbooks that assume a level of English proficiency not shared by many pupils. As a result, learners who are proficient in Kiswahili may face difficulties in learning (Kumar, 2023). Similarly, Brock-Utne (2007) argues that learner-centred pedagogy may not actually be possible in most African classrooms because of the limitations in the students’ and teachers’ skills in the international languages of instruction that are used.

Besides language constraints, the digital transformation journey itself is not easy for many in developing countries because of difficulties in accessing the required devices, lack of digital skills, and economic status that restricts the ability to own, maintain and actively use these devices. In these contexts, there are also barriers to providing inclusion for learners with challenges caused by different physical, neurological, cognitive and learning based abilities that would need special attention. A further challenge is created by the fact that most authors of textbooks learn in English but write books in Swahili. The entire journey involves accessing the internet which in some countries is still very expensive for the majority of citizens.

The objective of this study is to investigate how the dominance of English in digital literacy materials, ICT terminology and digital tools affects teachers and learners’ ability to effectively engage with digital transformation efforts in Tanzania. The main focus is on Swahili-speaking populations. Addressing these gaps would not only strengthen digital literacy but also promote equity, cognitive engagement, and long-term digital inclusion for Swahili-speaking communities. This leads to the following research question:How do language barriers, especially the use of ICT materials and terminology that is mostly in English, affect digital literacy acquisition and digital inclusion among Swahili-speaking teachers and learners in Tanzania?

Previous studies

Previous research has examined the use of digital tools in learning different languages (Alakrash & Razak, 2022; Nsyengula et al., 2025; Matiyenga & Kholalenyane, 2025), but there are only a few peer-reviewed studies on how using foreign languages in learning ICT can influence the digital literacy of the communities in question (Makalela & White, 2021). In Tanzania, English is used because of the lack, or in some situations the inadequacy, of the content in Swahili. Apart from the general reality, there is also a limited amount of Swahili content available for specialized and professional-level ICT teaching and learning.

A recent study by Smit, Swart and Broersma (2024) revealed the role of linguistic capabilities in digital inclusion, and Walizadah (2025) studied the significant role of mother tongue in education, arguing that mother tongue helps learners to understand concepts better, in this way creating a conducive environment for learning without anxiety. Studies such as this show that teaching in the learners’ mother tongue improves the learning outcomes. In the context of the present study, this entails digital skills, ICT competence, confidence, usage rates. Overall, teaching in the learners’ mother tongue has been found to enhance cognitive skills, sense of inclusion and academic performance (UNESCO, 2023), and the language of instruction has been proved to have a crucial influence for learning and equity (Crawford & Marin, 2021).

Localization surveys and policy papers stress that language of instruction is a key factor in inclusion (Meital & Jason, 2022). For individuals who use Swahili in their education and daily life, Swahili-based ICT tools, teaching and learning materials minimize language-based exclusion and democratise access to ICT, internet and information. This gives learners a chance to fully and meaningfully engage with digital tools. Previous research has identified localization as a key challenge for inclusion (Kerkhoff & Makubuya, 2022), since it involves processes of localizing software, creating Swahili language materials, building digital-language resources and evaluating how that influences inclusion and learning.

Methodology and data analysis

Data for this study was collected through semi-structured interviews and related observations in different educational institutions, including vocational level, in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma. The quadruple helix model was adopted to identify research participants, meaning that the study intentionally drew participants from four key stakeholder groups: society (teachers and students), academia (researchers), the private sector, and NGOs, to capture diverse perspectives. In practice, this guided a purposeful sampling where participants were selected based on their relevance, roles, and experience, rather than by chance. The sample size and composition were therefore determined by research needs and access, aiming for representation across the four groups rather than for statistical balance, with the goal of achieving depth and breadth of insight rather than generalizability.

Altogether 16 people were interviewed using semi-structured interview guides, and all of the participants gave their consent to use the results of the study. The results from these interviews were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. This approach is particularly suitable for this study because it enables the researcher to identify patterns across interviews, capture both the frequency and depth of participants’ concern and connect these insights to broader policy and educational implications, such as the development of Swahili-based digital literacy initiatives.

The researchers first familiarized themselves with all 16 interview responses, noting the mentioned key points, such as language barriers, code-switching, and infrastructure challenges. Statements were then coded by assigning them short labels representing their essence, and after this the responses with similar codes were grouped into broader themes. These themes included the education system, infrastructure, digital literacy, and technology design. The number of respondents mentioning each theme was also recorded to indicate prevalence. Finally, the themes were interpreted in relation to the research question, highlighting how language-related barriers affect teaching, learning, and technology adoption. This approach aligns with Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step method, involving familiarization, coding, theme development, review, definition, and reporting, and the current study explicitly reflecting coding, thematic grouping, quantification, and in-depth interpretation of systemic barriers and potential solutions.

Findings

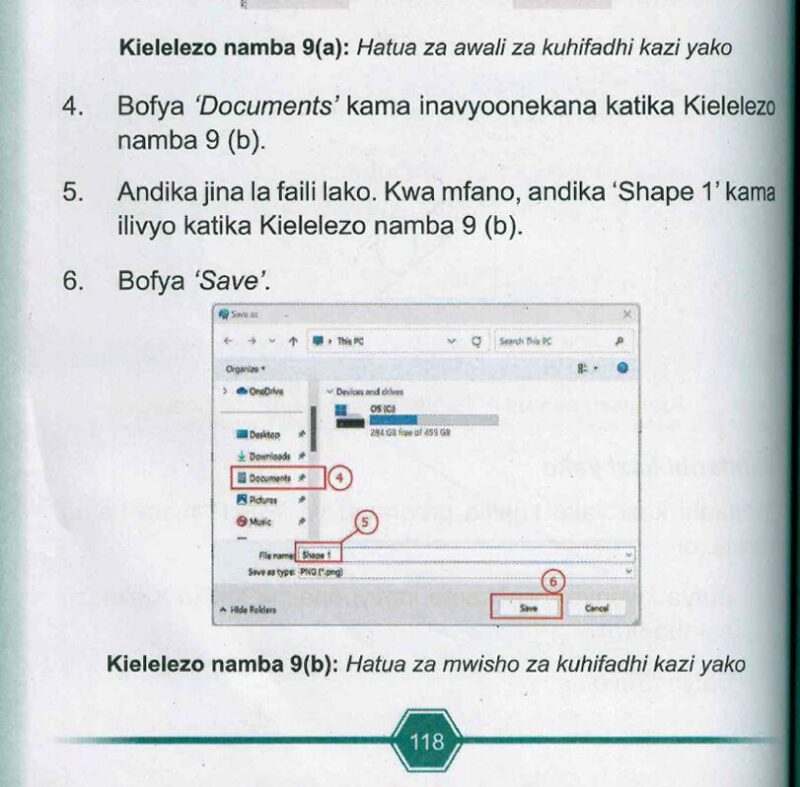

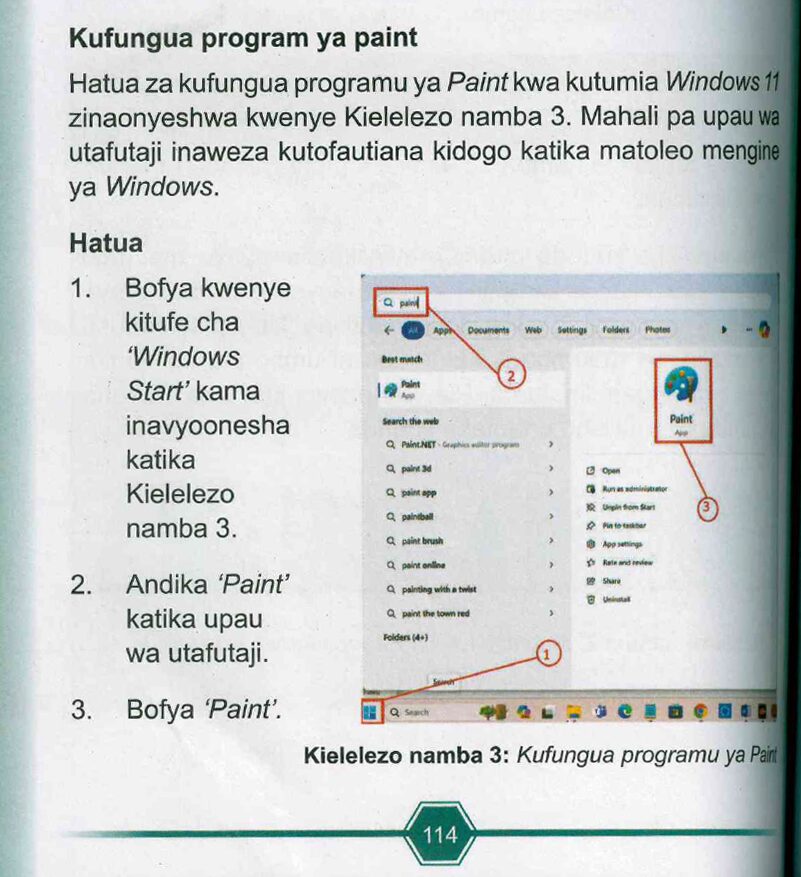

Some of the commonly-used digital literacy textbooks in Tanzanian public schools use mostly English. This makes it hard for those who only speak Swahili to understand and make use of these materials in their teaching and learning. What is more, the contextual relevance of ICT materials developed in English might not match local realities. For example, the classes may have to use ICT keyboards and terminology that are geared for using English and the materials may include photos of the same in teaching and learning textbooks, but at the same time some of the important practical information, such as computer-related instructions, are in Swahili.

Images 1 and 2 above show good examples of the confusing mix of languages in one textbook, based on which learners are expected to absorb the meaning in both languages and transfer the knowledge practically into how they use the devices. Having these two languages in one book or other material creates a combination of things, so that as the teachers and learners interact with the textbook, they constantly need to shift between languages because the language of presentation in the materials is different from the language of instruction and the language in which they think, making the transfer of knowledge from learning materials to screen a rather convoluted process. This dilemma of language and context affects both teachers and learners.

The systemic language gap in Tanzania’s digital transformation which the interviews highlighted can be categorized as follows:

| Theme/Category | Description/Summary | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Education system | ICT is taught in Swahili, but teacher training conducted in English | 13 |

| Infrastructure | ICT tools, online platforms, e-learning modules are mostly English-centric | 11 |

| Digital literacy | Teachers have difficulties in explaining ICT concepts in Swahili | 10 |

| Technology design | AI tools and learning platforms underrepresent Swahili | 8 |

Based on thematic classification of responses from the sixteen respondents, challenges related to the education system were the most frequent, with a large majority highlighting the dominance of English in ICT instruction and teacher training. Issues of infrastructure were also commonly mentioned, particularly the reliance on English-centric digital tools, platforms, and e-learning resources. More than half of the respondents pointed to digital literacy challenges, noting the teachers’ difficulties in explaining ICT concepts in Swahili, which in turn affects effective knowledge transfer. Although mentioned slightly less often, concerns about technology design were still significant, with several respondents observing that AI tools and learning platforms inadequately represent Swahili. In the context of issues examined by this study, AI systems can play a key role in addressing language mismatches in digital literacy training by enabling real-time translation, adaptive language support, and the development of high-quality ICT content in Swahili. AI-powered tools can localize interfaces, keyboards, and technical terminology more accurately than direct word-for-word translations, while also allowing learners to switch flexibly between Swahili and English as their proficiency develops. By supporting multilingual learning pathways that reflect classroom realities, AI systems can also reduce cognitive barriers, improve comprehension, and make digital literacy training more inclusive and culturally relevant for learners who are navigating mixed-language environments.

Teachers often switch between English and Swahili to compensate for the students’ difficulties, as existing localization efforts remain limited in scale and sustainability. On this, one of the interview respondents said: “In teaching ICT, we use both English and Swahili. Understanding depends on the learner for example fast and slow learners.”

Overall, the respondents emphasized that the lack of adequate Swahili ICT content, especially at professional levels, continues to disadvantage learners and restricts meaningful participation in the digital transformation. These challenges are systemic and multifaceted. In education, both ICT instruction and teacher training rely heavily on English, compelling teachers to code-switch in order to support students. This helps to support students by allowing teachers to clarifycomplex ICT concepts in Swahili, bridge gaps in understanding caused by English-only materials and make lessons more accessible to learners with varying language proficiency, thereby improving comprehension and participation.

Infrastructural and technological ecosystems remain dominated by English-first platforms and tools, limiting accessibility and reinforcing digital exclusion. As another respondent noted:

Most of the learning materials are in English, when most people do not speak it fluently. The need for Swahili is apparent, absence of Swahili for teaching and learning ICT and inadequacy of online resources is a reason why most learners are not coping well with online learning and parents are not able to engage with online content to support their children.

Several responses also highlighted the experience that even initiatives aimed at localization such as Kilinux and Localization Lab have had limited sustainability and reach. Kilinux is a localized Linux operating system developed in Swahili, while Localization Lab is an organization that works on translating and culturally adapting digital tools, software, and learning materials into local languages. Together, they help students by making ICT environments linguistically familiar and easier to navigate, reducing the cognitive burden of learning technology through a second language like English. By providing interfaces, terminology, and educational content in Swahili, these initiatives support clearer understanding, improve confidence, and enable learners and teachers to focus on digital skills themselves rather than struggling with language barriers, directly addressing the kind of digital exclusion highlighted in the study. For example, one respondent pointed out that “[t]here are adoption and sustainability challenges for these initiatives, a number of them remain weak, with limited impact or they are not functioning anymore.” Such responses show that Swahili language technologies still struggle with contextual accuracy, reducing their usefulness in educational settings.

There already are platforms that begin bridging the gap identified already in this study. These include Kolibri and Camara which help to navigate between English and Swahili in ICT and digital literacy training by providing localized software, training programs, and community-based technology initiatives that introduce core digital skills using Swahili while gradually familiarizing learners and teachers with English technical terms. In a similar way, Ubongo and Cyber Swahili support digital literacy by delivering educational and technology-focused content in Swahili through engaging, culturally relevant formats, helping learners understand digital concepts, build confidence, and participate more effectively in digitally mediated environments. Adopting Swahili in digital materials and ICT learning helps reduce language-based barriers which are often hidden, even as they are a major contributor to the digital divide in Tanzania. This makes it clear that Swahili-based tools would have the power to improve usability, as learners have a higher ability to adopt ICT when tutorials, guides and overall, more information is available in a familiar language. Many of the respondents saw the need for, and the benefits of, teaching in the learners’ mother tongue, for example, one of them said that

ICT learning should be also offered in Swahili for the speakers who use it as their main language. ICT Teachers should also have an opportunity to be trained in Swahili. Authors should publish more books in Swahili to expand the language and promote inclusive education. Instructional books should also go down to a sufficient Swahili level. We must be able to teach, show and learn in Swahili. This way we will reduce inequality in learning, which influences competence.

Overall, the findings suggest that language-related barriers to ICT integration operate at multiple, interconnected levels, from policy and training to classroom practice and technology development. The interviews suggest show that language is a systemic barrier for digital literacy in Tanzania, shaping how ICT is taught, learned, and experienced. Respondents described navigating a fragmented environment where instruction, textbooks, and platforms are predominantly English, while classroom interaction occurs mainly in Swahili. Teachers frequently code-switch to support comprehension, highlighting gaps in both educational materials and infrastructure. Overall, limited reach and sustainability of existing Swahili localization efforts further constrain learning. These insights indicate that language challenges are embedded across institutional, technological, and pedagogical systems, emphasizing the need for contextually relevant Swahili-based ICT resources and training to promote inclusive digital learning.

Discussion

This study shows that the language of instruction plays a critical role in shaping digital literacy and inclusion in Tanzania. These findings support the growing body of knowledge that emphasises the importance of language in digital learning environments. Even though many scholars have examined language learning through digital tools (see, e.g., Alakrash & Razak, 2022; Nsyengula et al., 2025; Matiyenga & Kholalenyane, 2025), fewer studies have explored how the language of instruction in ICT shapes digital literacy outcomes (e.g., Makalela & White, 2021). This study contributes to closing the gap by showing that the predominance of English in ICT curricula, software, and learning materials continues to marginalize Swahili-speaking learners in Tanzania.

The results of interviews highlighted how the language barriers are often embedded in ICT materials, with textbooks and digital resources mixing English and Swahili in ways that confuse rather than support learners. This finding aligns with evidence that the mother tongue plays a central role in understanding, and that it reduces anxiety and improves learning outcomes (Walizadah, 2025; UNESCO, 2023). For many participants, ICT tools and instruction that are based on English limited their ability to fully benefit from digital learning, echoing broader findings on the role of linguistic capabilities in digital inclusion (Smit, Swart & Broersma, 2024) and equitable education (Crawford & Marin, 2021).

The findings of this study also align with policy literature that emphasises the foundational role of language of instruction in creating a sense of inclusion (Meital & Jason, 2022). The respondents in the present study stressed that offering ICT content in Swahili, expanding Swahili-language instructional materials, and ensuring teacher preparedness in using Swahili at ICT instruction are critical steps toward democratizing access to digital skills. Without such efforts, the continued reliance on English risks excluding large segments of the population from meaningful participation in the digital transformation.

Overall, this study underscores the need for localized ICT resources, Swahili-based digital tools, and stronger support for mother-tongue ICT education. While language matters, digital literacy also depends on skills, infrastructure, and effective pedagogy. Localization affirms linguistic identity, counters digital colonialism, and enables users to engage with technology more confidently.

Conclusion, implications and recommendations

This study demonstrates that language is a central but often overlooked factor influencing digital literacy and ICT learning in Tanzania. The dominance of English in ICT curricula, digital platforms, and instructional materials creates persistent barriers for Swahili-speaking learners. While teachers attempt to bridge this gap through code-switching, the lack of adequate Swahili ICT resources continues to affect comprehension, confidence, and participation. Strengthening mother-tongue ICT instruction is therefore essential for improving digital inclusion and supporting Tanzania’s broader digital transformation.

Although existing initiatives have made progress, broader systemic change is needed, including a structured Swahili-based ICT curriculum and digital literacy programs for all government schools. Localized projects require sustained support to ensure maintenance, updates, and community participation, enabling Swahili speakers to create their own digital content and strengthen the Swahili digital ecosystem. The findings in this study further support the directions for education policy, digital inclusion, and technology design that has also been suggested by earlier research. Integrating Swahili into ICT instruction can improve learning outcomes, reduce inequality, and increase digital tool adoption. Prioritizing language in digital education strategies can accelerate national digital transformation while incorporating Swahili into software and AI systems can expand user reach and cultural relevance. In the end, addressing linguistic barriers is essential to ensuring that digital progress benefits all Tanzanians.

To ensure equal access, comprehensive Swahili-based ICT materials should be developed, and ICT teachers should receive Swahili-focused training to strengthen the quality of instruction. Sustainable localization of software, platforms, and low-resource AI tools is essential for better representation of Swahili and local contexts. This could be done by using a quadruple helix approach, to coordinate efforts among government, the private sector, academia, and NGOs so each actor plays a complementary role in supporting Swahili-based ICT initiatives. In this kind of an approach, the government provides policy and funding support, the private sector delivers technology and scalable solutions, academia contributes research and curriculum development, and NGOs ensure that community needs, inclusion, and capacity building are addressed. Working together, these four actors can help to ensure that localization efforts are sustainable, high-quality, and responsive to local contexts. Finally, ICT programs should systematically assess language-related barriers by integrating language monitoring into education and technology policies.

References

- Alakrash, H. M., & Abdul Razak, N. (2021). Technology-based language learning: Investigation of digital technology and digital literacy. Sustainability, 13(21), 12304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112304

- Brock-Utne, B. (2007). Language of instruction and student performance: New insights from research in Tanzania and South Africa. International Review of Education, 53, 509–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-007-9065-9

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative psychology, 9(1), 3-26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Crawford, M., & Marin, S. V. (2021). Loud and Clear: Effective Language of Instruction Policies for Learning. A World Bank Policy Approach Paper. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/loud-and-clear-effective-language-of-instruction-policies-for-learning

- Hajati, H. (2022). The Effect of ICT in the Curriculum. A new approach to children’s education quarterly, 4(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.22034/naes.2021.272954.1152

- Kerkhoff, S. N., & Makubuya, T. (2022). Professional development on digital literacy and transformative teaching in a low‐income country: A case study of rural Kenya. Reading Research Quarterly, 57(1), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.392

- Kumar, R. (2023). English language and digital literacy: Navigating the information age. Journal of International English Research Studies (JIERS), ISSN: 3048-5231, 1(2), 25-–31. https://languagejournals.com/index.php/englishjournal

- Makalela, L., & White, G. (Eds.). (2021). Rethinking language use in digital Africa: Technology and communication in sub-Saharan Africa (Vol. 92). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.2021.2015119

- Matiyenga, T. C., & Khoalenyane, N. B. (2025). The Potential of Digital Tools in Supporting the Teaching and Learning of African Languages. In O. Ajani (Ed.), Empowering Pre-Service Teachers to Enhance Inclusive Education Through Technology (pp. 183–214). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-8759-7.ch007

- Meital, K., & Jason, M. (2022). Language and coloniality report: Non-dominant languages in the digital landscape policy. Policy. https://pollicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Languages-Coloniality-Report.pdf

- Nsyengula, S., Emmanuely Haule, J., Mhagama, W., Okello, J. W. U., & Yassin, A. (2025). Challenges and Opportunities for Technology and Language Learning in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Classroom Action Research, 4(1), 7–14.https://doi.org/10.52622/jcar.v4i1.360

- Ntshauba, K. T. (2024). How Using English as the Medium of Instruction Affects Teaching and Learning at a TVET College: Lecturers and Students’ Experiences [Master’s thesis, University of South Africa].

- Smit, A., Swart, J., & Broersma, M. (2024). Bypassing digital literacy: Marginalized citizens’ tactics for participation and inclusion in digital societies. New Media & Society, 27(6), 3127–3145.https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231220383

- UNESCO. (2023). Why mother language-based education is essential. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/why-mother-language-based-education-essential

- Walizadah, F. (2025). The Role of Mother Tongue in Education. Journal of Learning and Development Studies, 5(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.32996/jlds.2025.5.1.5

Authors

Emma Nkonoki

Postdoc Researcher

Wilberforce Meena

HakiElimu (Right to Education) NGO