ABSTRACT: Through study crafting, students can actively shape study-related demands and resources to better align with their personal needs and abilities. The study reported in this article investigated study crafting and its links to student well-being among higher education students. A sample of 553 students from Häme University of Applied Sciences (HAMK) participated in a survey which assessed three dimensions of study crafting (i.e., increasing structural resources, increasing social resources, and increasing challenging demands) and several well-being variables. All three types of study crafting were found to be positively related to indicators of student well-being. Specifically, higher levels of crafting were linked to greater study engagement, study satisfaction, self-efficacy, and psychological flexibility, as well as lower levels of study-related burnout. These findings support the proposition of the SD-R theory, according to which proactive behaviors help students build personal resources, which in turn fosters their motivation and engagement. The findings of the present study highlight the importance of creating academic environments that encourage students to craft their studies. The findings also provide evidence in support of crafting interventions as a preventative approach to support student well-being. Future research should examine the bidirectional relationship between well-being and study crafting behaviors, explore crafting profiles to understand how students combine different strategies, and expand the conceptualization of social resources to include peer interactions. The current study contributes to the growing literature on proactive student behavior and underscores study crafting as a promising avenue for promoting student well-being.

Higher education students face various demands that may have detrimental effects on their mental well-being. In addition to balancing academic responsibilities, personal life, and potential employment, students are increasingly affected by rapid technological advancements and major global disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical conflicts. These factors have contributed to changing learning environments, increased mental health concerns, and growing uncertainty about future career prospects (e.g., Asikainen & Katajavuori, 2022; Salimi et al., 2023). While the results of the most recent Finnish Student Health and Wellbeing Survey (KOTT – Korkeakouluopiskelijoiden terveys- ja hyvinvointitutkimus) show slight improvements in higher education students’ study enthusiasm and study exhaustion compared to the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, over one third of students still reported experiencing study exhaustion (FSHS, 2025).

Within the increasingly digitized learning environment, students have greater autonomy to shape their studies according to their personal needs and interests. However, this autonomy also demands strong self-management skills to balance different demands, gain new resources, and take care of one’s well-being. The Finnish Student Health and Wellbeing Survey results indicated that students are increasingly more active in seeking help and that they could benefit from early interventions when facing challenges in their studies (FSHS, 2025). As higher education institutions have an important role in supporting students’ well-being and study ability, study crafting is one potential way to proactively promote student well-being.

Research in organizational psychology has established job crafting, that is, making self-initiated changes to their job demands and resources, as a proactive strategy for employees to enhance their psychological well-being and job performance. More recently, it has been proposed that also students can proactively shape their studies to promote their well-being (e.g., Mülder et al., 2022). In this study, I present the initial findings from a survey conducted during spring 2025 among students at the Häme University of Applied Sciences (HAMK), exploring the relationships between study crafting and various indicators of well-being. At HAMK, an annual student-experience questionnaire, LearnWell, is conducted for the first- and second-year students to monitor and support their learning experience and well-being. Since spring 2025, the LearnWell questionnaire has also entailed a study crafting scale to measure the students’ proactive efforts to shape their learning. Importantly, this provides new opportunities to explore the connections between study crafting and different well-being factors among higher education students.

The concept of study crafting

In the context of working life, job crafting is defined as “the changes that employees may make to balance their job demands and job resources with their personal abilities and needs” (Tims et al., 2012, p. 174). With Job Demands-Resource model (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) as the underlying framework, Tims et al (2012) proposed that people craft to increase their structural and social resources (e.g., learn new things, ask for feedback), to increase sufficiently challenging demands (e.g., take part in a new project), or to decrease hindering demands (e.g., avoiding mentally too demanding tasks). In this study, I focus especially on approach crafting (i.e., crafting focused on achieving positive outcomes; Zhang & Parker, 2019), as it has been found to be positively related to well-being. Meanwhile, the effects of avoidance crafting (i.e., attempting to avoid negative outcomes by decreasing hindering demands) on well-being remain inconclusive. While such crafting may work on the short term, over time it can inadvertently lead to the accumulation of additional demands, potentially resulting in detrimental impact on one’s well-being (for overview, see for example Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019; Rudolph et al., 2017).

More recently, the JD-R model has been adapted to the higher education context (Bakker & Mostert, 2024; Lesener et al., 2020). This has led to the development of the Study Demands-Resources model (SD-R; Bakker & Mostert, 2024), according to which higher education students encounter a range of study demands and resources that influence their well-being. Drawing on the concept of job crafting in the work environment, SD-R is used to consider how students may proactively shape their studies to create additional academic resources and to experience higher well-being. For instance, students may independently seek additional information on topics of their personal interest (increasing structural resources), request feedback on their assignments (increasing social resources), or engage in interesting side projects related to their studies (increasing challenging demands).

Enhancing well-being with study crafting

Research on job crafting has demonstrated various associations between job crafting and well-being. Specifically, job crafting has been found to be positively linked to well-being constructs such as work engagement, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy, and negatively associated with job burnout among employees who proactively shape their jobs (e.g., Rudolph et al., 2017; Silapurem et al., 2024).

Similarly, within the context of higher education, emerging empirical evidence suggests that study crafting is positively related to dimensions of student well-being. Study engagement refers to a positive psychological state where a student experiences study-related vigor, dedication, and absorption (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). In a weekly diary study, it was shown that students with more study resources were more engaged in their studies, which in turn fostered crafting to increase structural and social resources (Körner et al., 2021). Another study conducted among German university students found positive relationships between different types of study crafting, study engagement and general well-being, while it pointed to a negative relationship between study crafting and emotional exhaustion (Mülder et al., 2022). Study crafting has also been found to be associated with university students’ study satisfaction, especially when the students’ personal resources (e.g., self-efficacy, optimism, resiliency) were high (Tho, 2023). Therefore, personal resources, such as self-efficacy and psychological flexibility, also play an important role in study crafting. Self-efficacy reflects a student’s belief in their ability to successfully complete a task within a particular context (Bandura, 1997) and psychological flexibility refers to a student’s ability to adjust their actions and focus on what is really meaningful for them, even in emotionally challenging situations (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). According to the SD-R theory, engaged students with sufficient resources may experience gain spirals, that is, students with more resources are motivated to act in a proactive way to generate even more study and personal resources, and they experience higher study engagement (Bakker & Mostert, 2024). More recently, Körner et al. (2023) also showed that study crafting can be supported with interventions and that increased crafting was related to higher study engagement and lower exhaustion.

In the present study, the aim was to investigate how the study crafting scale functions and how study crafting is related to student well-being in the context of a university of applied sciences. More specifically, I explored how (1) study crafting works in its three dimensions (i.e., increasing structural resources, increasing social resources, and increasing challenging demands), and how these dimensions are related to (2) study engagement, (3) study satisfaction, (4) psychological flexibility, (5) self-efficacy, and (6) study-related burnout. The details of measuring these six elements are discussed further below.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The sample consisted of 553 HAMK students who answered the LearnWell study experience questionnaire during spring 2025 at degree program-specific sessions that were integrated into on-site or online teaching. In terms of background characteristics, 53.7% of the participants were female. The average age of the respondents was 28.8 years (SD = 8.1). As the survey targeted first and second year students, most of the respondents were first (55.5%) or second (41.2%) year students, but there was also a handful of students who had started their studies earlier. Most participants (78.3%) were full-time students. The participants were from various degree programs, with the largest groups coming from business administration (29.1%), business information technology (9.4%), computer applications (7.2%), and information and communication technology (6.5%).

Measurements

The participants answered the questionnaire either in English or Finnish. For questionnaire scales that did not have existing Finnish translations, the research team conducted back translations, and two experts in the field checked these translations. The response options for all the study items ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

(1) Study crafting was assessed with a nine-item scale adapted from Mülder et al. (2022) which was a further adaptation of the original job crafting scale (Tims et al., 2012). The scale consists of three subscales; each measured with three items. The items include, for example: “I proactively try to develop my capabilities” (increasing structural resources), “I ask my teachers for feedback on my study performance” (increasing social resources), and “If there are new possibilities for learning, I am one of the first to learn about them and try them out” (increasing challenging demands).

(2) Study engagement was measured with a three-item version of the Schoolwork Engagement Scale (Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). The three items were selected based on the previously validated Ultra-Short Measure for Work Engagement (UWES-3; Schaufeli et al., 2017). These items are: “When studying, I feel bursting with energy” (vigor), “I am enthusiastic about my studies” (dedication), and “I am immersed in my studies” (absorption). (3) Study satisfaction was measured with one item (“Overall, I am satisfied with my studies at HAMK”) adapted from Tho (2023). (4) Self-efficacy was measured with a five-item scale adapted for the higher education context (Parpala & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2012). This scale included statements such as: “I believe I will do well in my studies.” (5) Psychological flexibility was measured with a seven-item scale (Asikainen et al., 2018; Bond et al., 2013). This scale included items such as “I can study effectively even if I have worries.” (6) Study-related burnout was measured with the Study Burnout Inventory scale (SBI; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). This nine-item scale consists of three subscales: exhaustion (measured with four items, e.g., “I feel overwhelmed by the work related to my studies”), cynicism (measured with three items, e.g., “I feel that I am losing interest in my studies”), and inadequacy (measured with two items, e.g., “I used to have higher expectations of my studies than I do now”).

Analyses and Results

Prior to the main analysis, descriptive statistics were conducted to examine the properties of the variables, followed by confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to assess the validity of the measurement models. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (see Table 1). All the analyses were conducted in SPSS version 29 and R 4.5.1.

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | SC: Increasing structural resources | 3.9 | 0.8 | (.85) | |||||||

| 2. | SC: Increasing social resources | 3.1 | 0.9 | .49*** | (.77) | ||||||

| 3. | SC: Increasing challenging demands | 3.3 | 0.9 | .62*** | .57*** | (.75) | |||||

| 4. | Study engagement | 3.3 | 0.9 | .49*** | .38*** | .42*** | (.79) | ||||

| 5. | Study satisfaction | 3.8 | 1.0 | .33*** | .32*** | .19*** | .50*** | ||||

| 6. | Self-efficacy | 4.1 | 0.7 | .54*** | .36*** | .40*** | .48*** | .47*** | (.91) | ||

| 7. | Psychological flexibility | 3.4 | 0.8 | .34*** | .12** | .21*** | .35*** | .23*** | .54*** | (.90) | |

| 8. | Study-related burnout | 2.4 | 0.9 | -.26*** | -.12** | -.13** | -.35*** | -.45*** | -.52*** | -.46*** | (.89) |

Notes. N = 550-553. SC = study crafting. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. Cronbach’s alphas appear in brackets along the diagonal.

The three-factor model indicated an acceptable fit for the study crafting scale, χ2 (24) = 89.10, p < .001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.05. The three-factor model showed a better fit than a one-factor model where all the crafting items loaded into the same factor, χ2 (27) = 317.95, p < .001, CFI = 0.81, TLI = 0.75, RMSEA = 0.17, SRMR = 0.09. Cronbach’s alphas for the study crafting subscales ranged from .75 to .85, and for the well-being variables from .79 to .91, demonstrating good internal consistency.

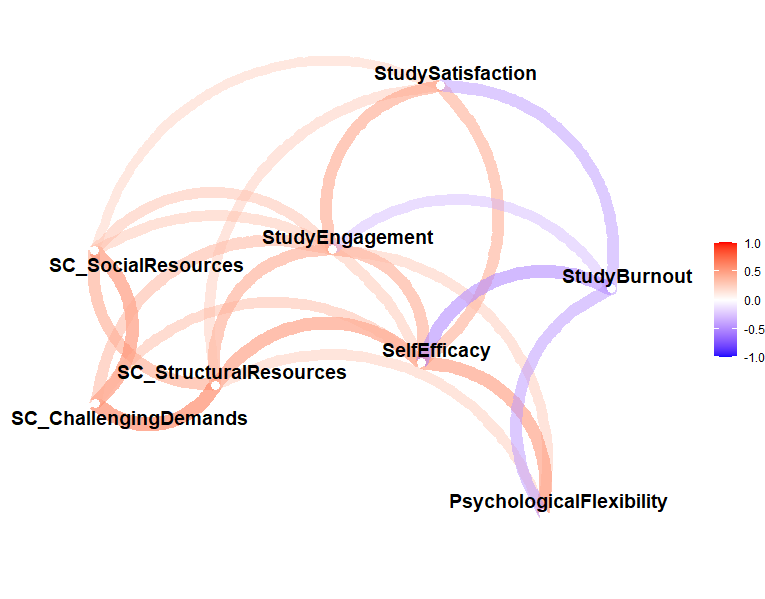

Overall, students reported the highest levels of crafting aimed at increasing structural resources and the lowest levels of crafting aimed at increasing social resources. Regarding the associations between study crafting and different well-being variables, the findings show that all three types of study crafting were linked to higher well-being (i.e., the elements measured with questions related to higher study engagement, study satisfaction, self-efficacy and psychological flexibility, and lower study-related burnout). All means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between the study variables are presented in Table 1 and statistically significant correlations above 0.3 are shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

In line with previous research, study crafting was found to be related to higher well-being. Students who reported that they craft to increase their structural and social resources and challenging demands also reported higher levels of study engagement, study satisfaction, self-efficacy and psychological flexibility, and lower levels of study-related burnout. All three crafting dimensions (increasing structural resources, increasing social resources, and increasing challenging demands), showed positive medium-sized correlation with study engagement, which is in line with the SD-R theory that proposes that engaged students are motivated to proactively craft their studies, resulting in potential gains in higher engagement, well-being, and resources (Bakker & Mostert, 2024). Positive medium-to-high correlations between self-efficacy and all three study crafting dimensions also suggest important links between students’ personal resources and proactive behavior. Students who feel confident in managing their studies are more likely to proactively adjust their study demands and resources by crafting their studies. There were also medium-to-large positive correlations between the study crafting dimensions, indicating that students who engage in one type of crafting are also often motivated to engage in other types of crafting to seek out different resources.

The pedagogical community can support study crafting by students

Study crafting enables students to be active participants in their academic journey and to make their studies more enjoyable and meaningful. Students may craft their studies by nurturing their curiosity and seeking additional resources about topics that interest them, so that they can extend their knowledge and understanding beyond the study curriculum. Feedback and dialogue also play a central role. Actively seeking feedback on one’s assignments and engaging in discussions with teachers and peers can provide inspiration and spark new ideas. Moreover, students can participate in projects outside of regular coursework. Involvement in student associations, multidisciplinary initiatives, and periods of studying abroad allow them to apply their knowledge in collaborative situations that are often set in real-world contexts, promoting important working life skills and fostering a sense of community.

While study crafting is an individual strategy, teaching staff can support students in their efforts to align their studies with their personal needs and interests by fostering an environment where study crafting is supported and encouraged. Teachers can allow students to make choices regarding their project topics, share interesting resources about their field, and encourage students to take a deeper look into topics that they are interested in. Providing constructive feedback that is specific and actionable helps students in understanding how to improve their work. Moreover, when teachers seem easily approachable, students feel more comfortable asking questions, seeking guidance, and discussing their academic goals. This helps to create a supportive atmosphere that empowers students to take risks and explore new ideas. In addition, designing assignments that challenge students to think critically and encourage them to take initiative promotes deeper engagement. Hence, recognizing and encouraging students’ study crafting helps to cultivate a culture that values growth and curiosity.

Finally, students may benefit from training and interventions regarding study crafting. Such training sessions can offer students opportunities to become more aware of their study-related interests, strengths, and goals. Additionally, this gives them a chance to learn about various study crafting techniques and to put these skills into practice in their daily life as students.

Future research

The current study offers important initial insights on the study crafting behaviors of students in the context of a university of applied sciences and considers the relationship of these behaviors on their engagement and well-being. Additionally, it provides multiple promising directions for future research. Indeed, the present study makes it apparent that future research should consider conducting profile analyses to identify distinct patterns of crafting behaviors among students in order to better understand how students may engage in multiple forms of crafting and what are the effects of such crafting on their well-being. Future research should also focus on investigating the bidirectional relationship between study crafting and different well-being constructs. While crafting may enhance well-being, the psychological well-being of students may also influence their capacity and motivation to craft their studies. Longitudinal and mixed-method research designs could provide deeper insights into these dynamic interactions. Finally, it must be noted that this study has measured crafting for increasing social resources only in terms of interactions with teachers. However, also peer relationships represent a significant source of social support. Because of this, future studies should expand the scope of crafting for social resources to include peer interactions.

References

- Asikainen, H., Hailikari, T., & Mattsson, M. (2018). The interplay between academic emotions, psychological flexibility and self-regulation as predictors of academic achievement. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(4), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1281889

- Asikainen, H., & Katajavuori, N. (2022). First-Year Experience in the COVID-19 Situation and the Association between Students’ Approaches to Learning, Study-Related Burnout and Experiences of Online Studying. Social Sciences, 11(9), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090390

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Mostert, K. (2024). Study Demands–Resources Theory: Understanding Student Well-Being in Higher Education. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09940-8

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. (pp. ix, 604). W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

- Bond, F. W., Lloyd, J., & Guenole, N. (2013). The work-related acceptance and action questionnaire: Initial psychometric findings and their implications for measuring psychological flexibility in specific contexts. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(3), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12001

- FSHS. (2025). Enthusiasm for studying has grown among higher education students, students also active in seeking help with study-related issues. https://www.yths.fi/en/news/2025/enthusiasm-for-studying-has-grown-among-higher-education-students-students-also-active-in-seeking-help-with-study-related-issues/

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

- Körner, L. S., Mülder, L. M., Bruno, L., Janneck, M., Dettmers, J., & Rigotti, T. (2023). Fostering study crafting to increase engagement and reduce exhaustion among higher education students: A randomized controlled trial of the STUDYCoach online intervention. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 15(2), 776–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12410

- Körner, L. S., Rigotti, T., & Rieder, K. (2021). Study Crafting and Self-Undermining in Higher Education Students: A Weekly Diary Study on the Antecedents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), Article 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137090

- Lesener, T., Pleiss, L. S., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2020). The Study Demands-Resources Framework: An Empirical Introduction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), Article 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145183

- Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2019). A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1527767

- Mülder, L. M., Schimek, S., Werner, A. M., Reichel, J. L., Heller, S., Tibubos, A. N., Schäfer, M., Dietz, P., Letzel, S., Beutel, M. E., Stark, B., Simon, P., & Rigotti, T. (2022). Distinct Patterns of University Students Study Crafting and the Relationships to Exhaustion, Well-Being, and Engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.895930

- Parpala, A., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2012). Using a research instrument for developing quality at the university. Quality in Higher Education, 18(3), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2012.733493

- Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

- Salimi, N., Gere, B., Talley, W., & Irioogbe, B. (2023). College Students Mental Health Challenges: Concerns and Considerations in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 37(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2021.1890298

- Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.11.001

- Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M., & De Witte, H. (2017). An Ultra-Short Measure for Work Engagement. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000430

- Silapurem, L., Slemp, G. R., & Jarden, A. (2024). Longitudinal Job Crafting Research: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 9(2), 899–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00159-0

- Tho, N. D. (2023). Business students’ psychological capital and quality of university life: The moderating role of study crafting. Education + Training, 65(1), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2022-0176

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2332

Authors