Research on bioclimatic design suggests that it is possible to make use of microclimates in building design and in this way achieve thermal comfort while saving energy (Cabeza & Chàfer, 2020; Dounis & Caraiscos, 2009; Genovese & Zoure, 2023; Manzano-Agugliaro et al., 2015). In this type of design, the most fundamental factors of microclimates that should be considered include solar radiation and local wind conditions, that is, air flow. Solar radiation is taken into account to mediate incoming sunlight and the solar heat gain of the building, while local air flow can be utilised to ventilate the building. The combination of these two factors can assist in regulating the occupants’ thermal comfort, in leveraging natural environmental conditions, and in decreasing mechanical means of ventilation and the use of energy. For both solar and wind factors, the orientation of the building openings, such as windows, plays a crucial role. In terms of solar factors, openings generally need to be oriented toward the equator – although this is most effective in temperate climates – and appropriate shading methods need to be applied so that solar heat gain can be maximised in winter and minimised during summertime (Roaf et al., 2007). To make use of the environmental wind conditions, on the other hand, the building openings should ideally be oriented toward prevailing wind directions to facilitate effective cross-ventilation throughout the interior spaces.

Bioclimatic design displays parallels with vernacular architecture, that is, traditional ways in which communities housing themselves adapt to social and environmental contexts (ICOMOS, 1999). Historically, vernacular architecture embodies bioclimatic principles, as traditional building practices have evolved in response to regional climates, available materials, and cultural needs. Bioclimatic design primarily focuses on the relationship of the systemic organisation of the buildings (including technical building services), local environments, and the occupants of the buildings, to ensure the thermal performance of the buildings works for the occupants’ comfort. Bioclimatic design can also further aid climate adaptation and sustainability beyond the immediate surroundings of the building, responding to the current climate challenges. However, these second-order effects need more attention as the influence of climate change on our daily lives is increasing, and our living environments need to adapt to these changes. These second-order effects of bioclimatic design can be amplified by more actively making use of ecological elements in the bioclimatic design of buildings and neighbourhoods.

Bioclimatic design for low-density detached houses

ILPI – Ilmastokestävät pientaloalueet (Climate-resilient Suburban Areas) project by HAMK investigates climate resilience of suburban low-density residential areas in Finland. In designing low-density residential environments, the most common ecological elements that need to be taken into account include vegetation and water flows. Vegetation needs to be considered not only for climate-smart thermal comfort (e.g., for shading), but also for climate mitigation, such as carbon sequestration capacities and biodiversity. Water flows, on the other hand, need to be taken into account to improve climate adaptation (e.g., for better stormwater management) and resource conservation. When designing water flow management, the vegetated areas and the pervious areas can be considered in terms of the residents’ needs and the constraints of the area. That is, planning the composition of the areas can take into account, for example, how some residents may want less vegetated areas for some activities other than gardening. At the same time, the planning can also consider the spatial, social, and ecological contexts of the area, for example, when some vegetation might not be preferred due to safety reasons, or vegetation may need to be located in certain ways due to some regulatory or cultural reasons. There may also be a need to arrange the vegetated and pervious areas in a specific composition because of how the specific topography of the region influences local water flow in case of heavy rain. These considerations, then, also take into account climate adaptation and mitigation. Currently, the proportion of vegetated pervious areas of detached houses is decreasing, leaving too little space to accommodate large trees and increasing rainwater runoff in the plots, which may overwhelm drainage systems and increase the risk of flooding and waterway pollution. These trends need to be understood and managed in multiple scales, not only on the scale of individual plots, but also on the scale of entire housing blocks and neighbourhoods. Also the residents’ needs for dwelling should be considered to ensure climate adaptation and sustainable living environments. The objective of the ILPI project is to help integrate all of these concerns in low-density detached housing design.

A nation-wide survey was carried out at the beginning of the ILPI project in 2024 to map the current state of the residents’ housing use and requirements in low-density areas in Finland. The results from this survey show that the typical elements residents want for a detached house comprise of a house, vegetation, a garage for two cars, terraces, a shed, a waste storage area, and a composting area. Some of these structures, such as the house itself – more precisely openings such as windows – and the terraces, are more sensitive to orientations than other structures. This is because they need to reflect the residents’ needs and their thermal comfort. For Finland, the recommendation is that the windows of the house should face south in order to receive the most consistent sunlight throughout the day. With south-facing windows, the residents are able to let the lower winter sun through and regulate the higher summer sun with shades or coatings. Also the terraces can be placed on the south side for consistent sun. If the house and its terraces face west, they may require more substantial vertical shading to regulate low-angle western evening sun and prevent overheating of the spaces and the resulting thermal discomfort, especially in summer. Here, deciduous trees can function as optimal vertical shades, as they can shade low-angle sun in the summer while letting the sun through in the winter. For such design, it would be ideal for the trees in the plot to include at least one large tree because it can simultaneously provide substantial shading and promote climate mitigation. Although the effect may not seem significant for a single plot, the cumulative effect on the scale of a street, a block or a neighbourhood can be notable if all plots in the area use similar solutions.

The layouts of these elements in detached house design also depend on another decisive parameter – the location of the garage on the plot. In reality, the location of the garage may have to be considered first, since driving paths must be designed in relation to the location of the street. This includes designing enough space for the cars to park, turn, and get in and out of the garage. To minimise impervious surfaces, driving paths can double as parking space for one of the cars. As these layouts are designed, it is worth acknowledging how much the route from the road to the plot affects how the layout of the elements on the plots can be designed. Taking into account the optimal layouts for individual plots can then be reflected in the urban planning practice for entire housing areas.

Using sun path simulation as a design tool

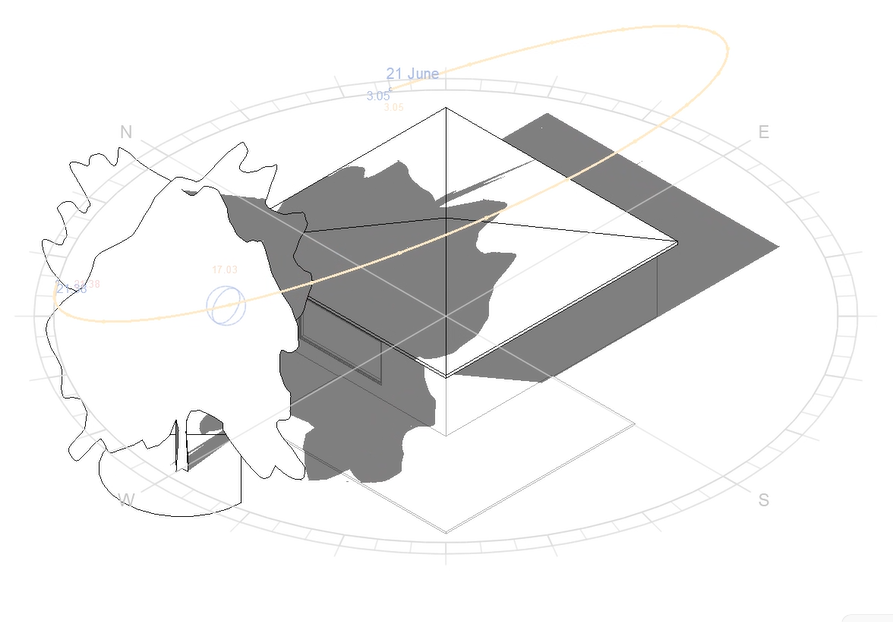

As discussed above, for optimal bioclimatic design the orientations of houses and their terraces need to reflect the residents’ needs and take into account their thermal comfort. Sun path simulation is a simple way to visualise how the orientation of structures affects their temporal solar exposure. In Finland, the temporal path of the sun differs drastically from winter to summer (video 1a), which can be taken into account by positioning windows according to the residents’ preferences regarding sunlight and solar heat gain throughout the year. For the summer months, south and west-facing openings should be carefully considered in terms of excessive solar heat gain, especially because of the rising global temperature. On the summer solstice, the south-facing window is exposed to the sun for long hours throughout the day (video 1b), which can be shaded with horizontal shades such as deeper eaves (video 2a), or light shelves. If needed, vertical shading elements can be added using pergolas or trees (video 2b).

On the other hand, in the summer the west-facing window can allow the low-angle sun to penetrate deep into the space from the late afternoon onwards (video 3), overheating the space inside. It is more difficult to shade from the low-angle sun only with horizontal shades (video 4a). Instead, this requires vertical shading elements (video 4b) which can simultaneously provide shade to terraces, to the internal spaces, and to the external surfaces of the house, depending on the relative locations of all components. Furthermore, terraces can be located based on the residents’ preferences. For example, terraces can be located on the south side of the house to allow the sun for most of the day, on the east side for morning sun, or on the west side of the house to allow for evening sun.

As mentioned above, a large deciduous tree in the plot can provide multiple benefits. A tree provides shading and in this way modulates solar radiation appropriately for the seasonal changes of sun paths. This results in the residents’ thermal comfort and energy conservation, but it also helps to improve air quality, stormwater management, and carbon sequestration. Thus, accommodating a large deciduous tree in each plot can provide wide-ranging benefits for the house, and if majority of the plots in the area could accommodate large trees, these effects could be amplified in scale when extended to the scale of a street, block, or the entire neighbourhood. Additionally, the sun path simulations above show that the shading benefit that a tree can provide for a house is sensitive to the relative orientations of the two. These observations indicate that placing a large tree on the southwest side of the house (and terraces) would be optimal, and this spatial configuration of a house and a tree can be used as a defining unit when thinking about the optimal layout options for the required components on a plot. However, accommodating a big tree in each plot requires not only disseminating knowledge and promoting it to the residents, but also sophisticated regulatory frameworks for local authorities that can balance the residents’ needs, the needs for climate adaptation and mitigation, and the planet’s boundaries. To further reinforce the second-order effects of bioclimatic design, regulatory frameworks could be adjusted by modifying existing policies and by adopting new measures, as regulatory measures could be interrelated to each other and to various external factors. For example, this would mean considering, in relation to each other, the regulations regarding maximum floor area ratio or building coverage ratio and the requirements for minimum vegetated and/or pervious areas. Moreover, these regulations would have to reflect the changing needs of the residents and the societies, and take into account their broader spatial implications, such as climate adaptation and mitigation capacities in the scale of neighbourhoods, districts, regions, and ultimately the planet. Such multifarious complexity will continue to be investigated by ILPI project.

References

- Cabeza, L. F., & Chàfer, M. (2020). Technological options and strategies towards zero energy buildings contributing to climate change mitigation: A systematic review. Energy and Buildings, 219, 110009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110009

- Dounis, A. I., & Caraiscos, C. (2009). Advanced control systems engineering for energy and comfort management in a building environment—A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 13(6–7), 1246–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2008.09.015

- Genovese, P. V., & Zoure, A. N. (2023). Architecture trends and challenges in sub-Saharan Africa’s construction industry: A theoretical guideline of a bioclimatic architecture evolution based on the multi-scale approach and circular economy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 184, 113593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113593

- ICOMOS. (1999). Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/vernacular_e.pdf

- Manzano-Agugliaro, F., Montoya, F. G., Sabio-Ortega, A., & García-Cruz, A. (2015). Review of bioclimatic architecture strategies for achieving thermal comfort. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 49, 736–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.095

- Roaf, S., Manuel Fuentes, & Stephanie Thomas. (2007). Ecohouse: A design guide (3rd edn). Architectural Press.

Authors